Why Didn't God Ban Slavery?

By Lawren Guldemond

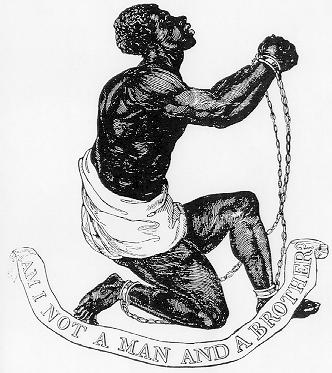

In several of his letters, the Apostle Paul gave instruction that Christian slaves should be obedient to their masters, and Christian masters should be fair in ruling over their slaves.[1] Those letters are part of the Bible. Adversaries like to point this out and argue that the God of the Bible is in favour of slavery, and is therefore despicable and morally inferior to modern secular humanists.

If God is real and good, and the Bible is His Word, why doesn't the Bible contain denunciations of slavery rather than apparent endorsements?

First of all, the Bible does prohibit slavery in its absolute form. Exodus 21:16 proscribes the death penalty for those who enslave others, and for those who buy the kidnapped victims of such slave traders. In his first epistle to Timothy, Paul reaffirms this by including enslavers in a list of denunciations (I Timothy 1:10).[2] Deuteronomy 23:15-16 prohibited giving runaway slaves back to their masters, and commanded that they be given refuge instead. If a master struck a slave and knocked out a tooth or blinded an eye, the slave went free (Exodus 21:26-27). If a master beat a slave to death, it was commanded that the master be punished (Exodus 21:20). Furthermore, the laws of Jubilee (Leviticus 25) mandated that everyone in bondage be set free every seventh year. Taken together, these limitations prevent the kind of unbridled despotism that slave owners practised in the antebellum American South. Observe that every one of these commandments was violated by those who ran the transatlantic slave trade and the southern cotton plantations.

The "slavery" allowed for in the Bible is not equivalent to the absolute slavery imposed on Africans in the New World.[3] The biblical model is better understood as indentured servitude. In a typical case, a free man who is struggling and failing to make a living as an independent farmer on his own land might decide to become a bondservant to a prosperous farmer in order to gain food security. According to Paul Copan:

We should compare Hebrew debt-servanthood (many translations render this "slavery") more fairly to apprentice-like positions to pay off debts—much like the indentured servitude during America's founding when people worked for approximately 7 years to pay off the debt for their passage to the New World. Then they became free.[4]

It was a provision for the welfare of those who became bankrupt, that they should become servants to others who were financially stable and competent and could therefore provide for them, in return for their service in labour. Biblical jubilee laws (Leviticus 25) mandating debt forgiveness, release of bondservants, and the restoration of farmland back to the family that had sold it all served to prevent those who fell into debt bondage from being trapped in that estate permanently. (For further reading, see the lengthy discussion of the nature of servitude in Hebrew society and the Gentile societies that surrounded them in the Ancient Near East (ANE) on Glenn Miller's Christian ThinkTank website).

Notwithstanding these mitigating factors, the objections will persist—granting that the Bible doesn't allow unmitigated slavery, why does it yet allow mitigated slavery (indentured servitude)? Why didn't God just tell the apostle Paul to declare that everyone should be free and no one should ever be held in bondage and compelled to labour for another?

Notwithstanding these mitigating factors, the objections will persist—granting that the Bible doesn't allow unmitigated slavery, why does it yet allow mitigated slavery (indentured servitude)? Why didn't God just tell the apostle Paul to declare that everyone should be free and no one should ever be held in bondage and compelled to labour for another?

I believe one of the key reasons is that the true hope for human felicity lies not in deliverance from unjust or unequal socioeconomic conditions, but rather in obtaining peace with God and eternal life, and in learning to be content and gracious in spite of persisting inequities.

There will always be some economic hierarchy, which means that some people will be the masters or bosses and exercise power over others who are economically dependent on them. In our modern Western societies, we have greatly reduced the disparities of power in the master-servant (employer-employee) relationship, providing the "servant" with liberty and freedom unmatched in all of history. Even those at the bottom strata of our economic hierarchy live in freedom. As far as economic freedom, equality and liberty go, our Western societies are as good as it gets. Yet are we content and happy? Consider the Occupy Wall Street movement, the Other 99% meme, and how common it is for people to despise and grumble about their bosses. We have achieved about all there is to achieve in personal liberty for all, and yet we are not satisfied. There are 192 countries in the world today. Tell me which of them is a perfect utopian paradise where all is fair and just and equitable and everyone is content, happy, and living in harmony. I assert that if we haven't been able to achieve utopia by this point in history, we never will. It's an impossible dream. So if your tranquillity and joy is dependent on living in the perfect political order, you may as well despair and give up now. The attainment of felicity cannot be achieved if it is dependent on dwelling within a perfect socioeconomic system.

While freedom and equality cannot bring us perfect bliss, it is true that living in a state of freedom is a very pleasant way to live. Freedom is something to cherish and be grateful for. So even if freedom cannot make us totally happy, why didn't God command that every servant should be set free?

It is important to realize that economic freedom and liberty are matters of degree; no earthly society can ever afford and provide complete freedom to all. All of us who have houses with mortgages are legally obliged to keep working and earning money to hand over to the bank. If we don't, the authorities will help them seize whatever assets we have, which would seriously impair our economic freedom and liberty. Those who borrow hefty student loans to finance a professional education are similarly indebted. Now, we have the liberty to go find a workplace of our choice, but we do have to work hard somewhere; we cannot just go lounge around by the lake perpetually and shirk work, because we have debts to pay. Even in our society, we still throw people into prison for being unable to repay money which others had loaned to them; although we only do it when there is legal evidence of wilful fraud and embezzling, yet still we do it. Everyone who enlists in the military puts themselves into a position of subordination to command that has a lot in common with ancient servitude. If you go AWOL, the military will put you in one of its prisons. Your boss cannot punish you for skipping work, but he can fire you for it. Since you need the money, you are trapped in a power relationship where you need to get his permission to skip work for a few days if you want to go on a journey somewhere. And, of course, there are taxes. We are required to devote about one in four working days to producing the tribute to be exacted from us by our country and community. If you don't pay your taxes, we will ultimately throw you in jail. So while our society affords its members a very high degree of economic liberty and mobility, it's still not absolute freedom. No society can provide absolute freedom for all; there must of necessity be some sort of economic power relationships.

As noted at the beginning of this article, the Apostle Paul instructed Christians to comply with the master-servant structures of the world in which they lived. These relationships did not entail the complete abnegation of freedom and dignity that was seen in New World slavery, but they did curtail freedom to a degree that we would find unacceptable for ourselves. The New Testament portion of the Bible, which provides instruction to the Christian Church, does not stipulate exactly what the terms of master-servant relationships should be. Neither does it stipulate any other details of the form of the political economy; it does not mandate democracy, monarchy, or imperial republicanism. Political arrangements grow out of community and traditions, and adapt to the changing realities of civilization. The Bible is the Word of God for all people for all time. Its purpose is to instruct people in transcendent truths that transcend political orders; it is not to establish the perfect political order, which is a pipe dream. The Bible instructs Christians to be good to others, no matter which side of an economic power relationship they are on, no matter how just or unjust the structure of the arrangement may be (Ephesians 6:5-9).

Christians have hope and joy not because they were born into a perfectly just society, nor because they created a perfectly just society for themselves, but rather in spite of the realities of inequality, injustice, and economic power relationships (Philippians 4:11-13). They have hope and joy because they have peace with God through the work of Jesus Christ.

[1] See Ephesians 6:5; Colossians 3:22, 4:1; 1 Timothy 6:1; 2 Timothy 2:9.

[2] This word is variously translated into English as "enslavers," "manstealers," or "kidnappers."

[3] "From a global cross-cultural and historical perspective, however, New World slavery was a unique conjunction of features . . . In brief, most varieties of slavery did not exhibit the three elements that were dominant in the New World: slaves as property and commodities; their use exclusively as labor; and their lack of freedom . . ." David Levinson and Melvin Ember, eds., Encyclopedia of Cultural Anthropology, (New York: Henry Holt, 1996), 4:1190f., quoted in Glenn Miller, "Does God Condone Slavery in the Bible?," The Christian ThinkTank, last modified March 18, 2004, accessed March 24, 2015, http://christianthinktank.com/qnoslave.html (emphasis Miller's).

[4] Paul Copan, "Does the Old Testament Endorsse Slavery? An Overview," Enrichment Journal, accessed March 24, 2015, http://enrichmentjournal.ag.org/201102/201102_108_slavery.htm.cfm. For further reading, there are two more articles in Copan's series: "Does the Old Testament Endorse Slavery?" and "Why Is the New Testament Silent on Slavery—or Is It?"